The Process of Becoming

Sunah Choi shows me around her studio. I’m in London, she’s in Berlin: we’re linked by the small glowing rectangle of her phone. She zooms in on a group of geometric wooden sculptures – which she calls ‘maquettes’ – she’s in the midst of making.

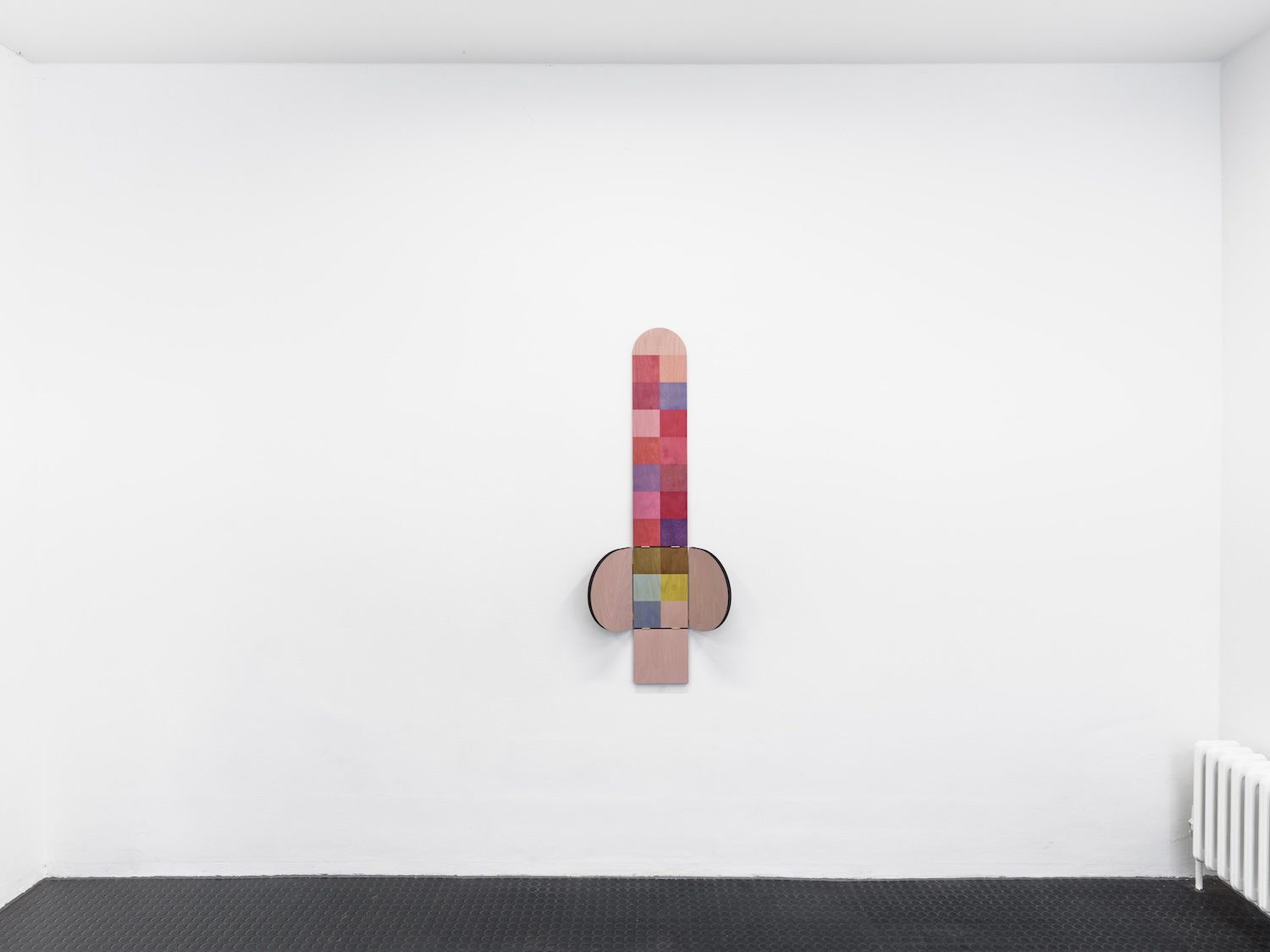

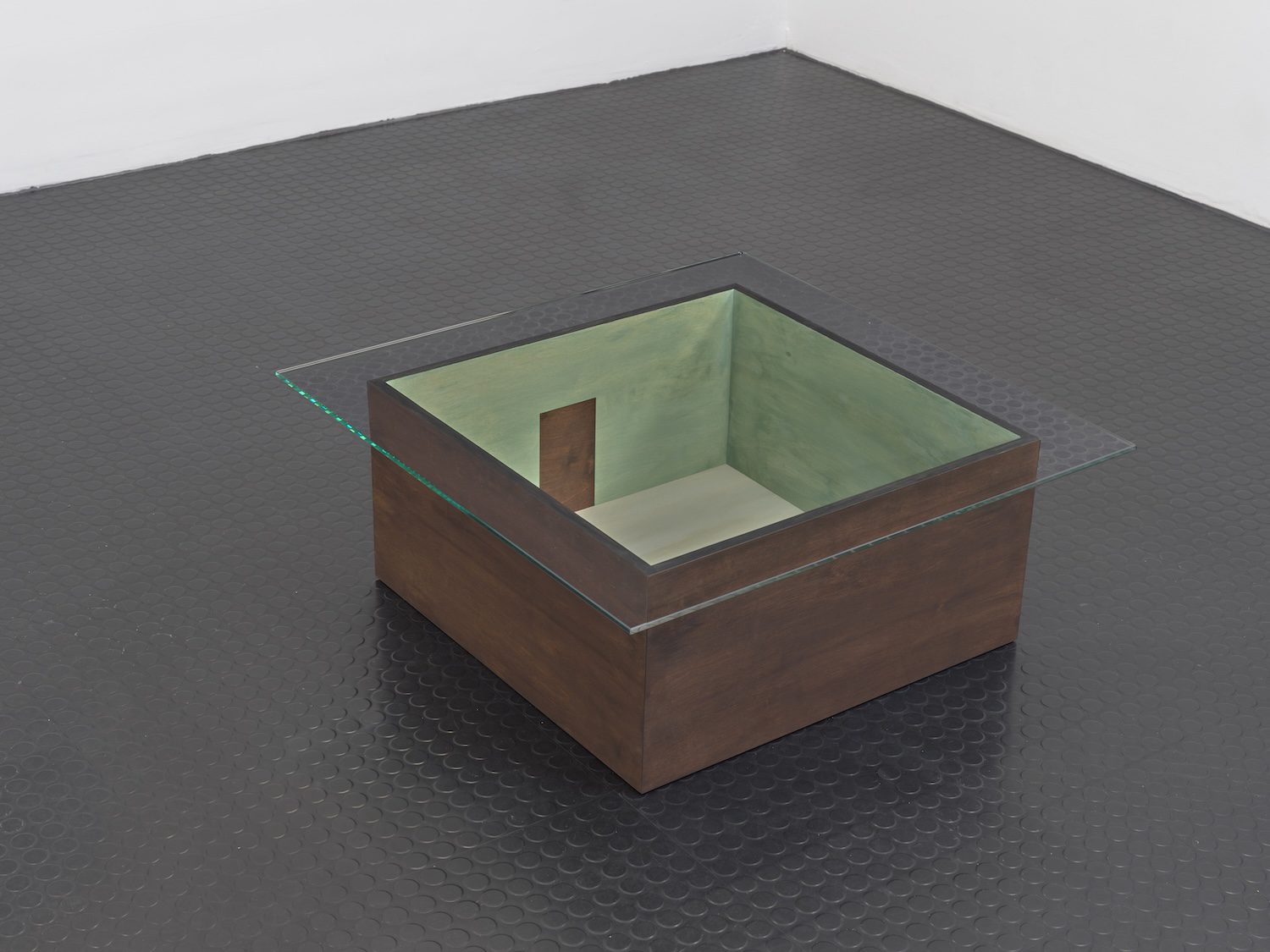

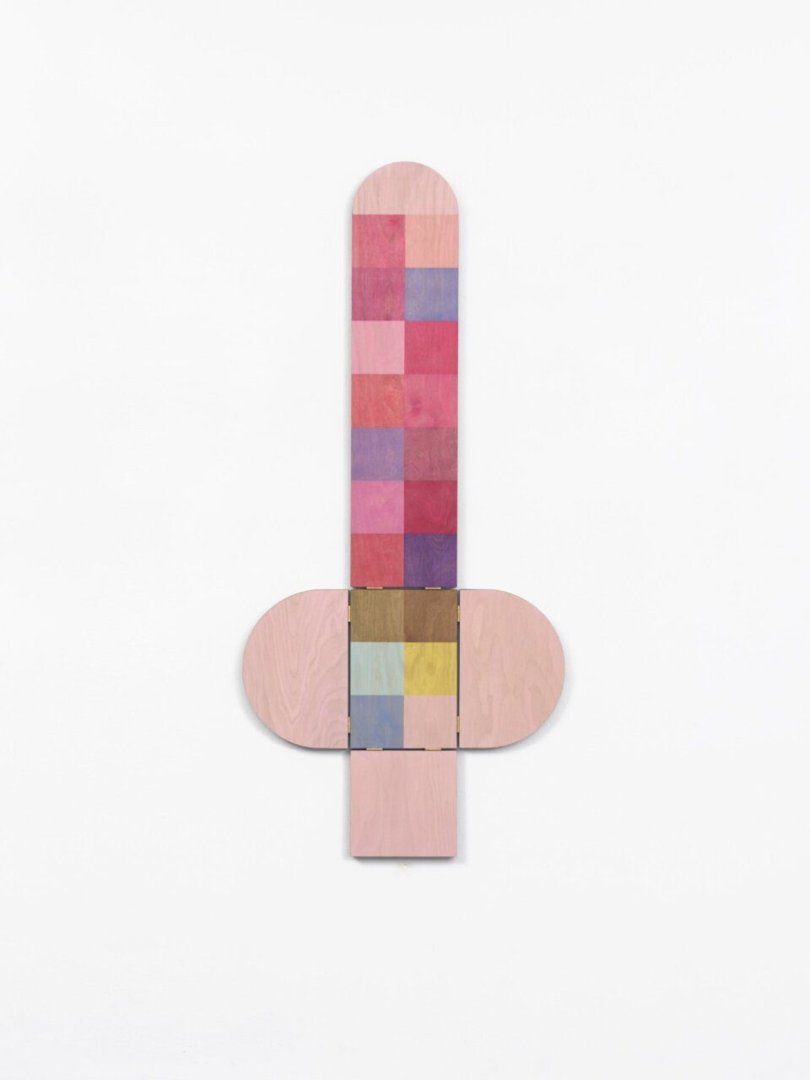

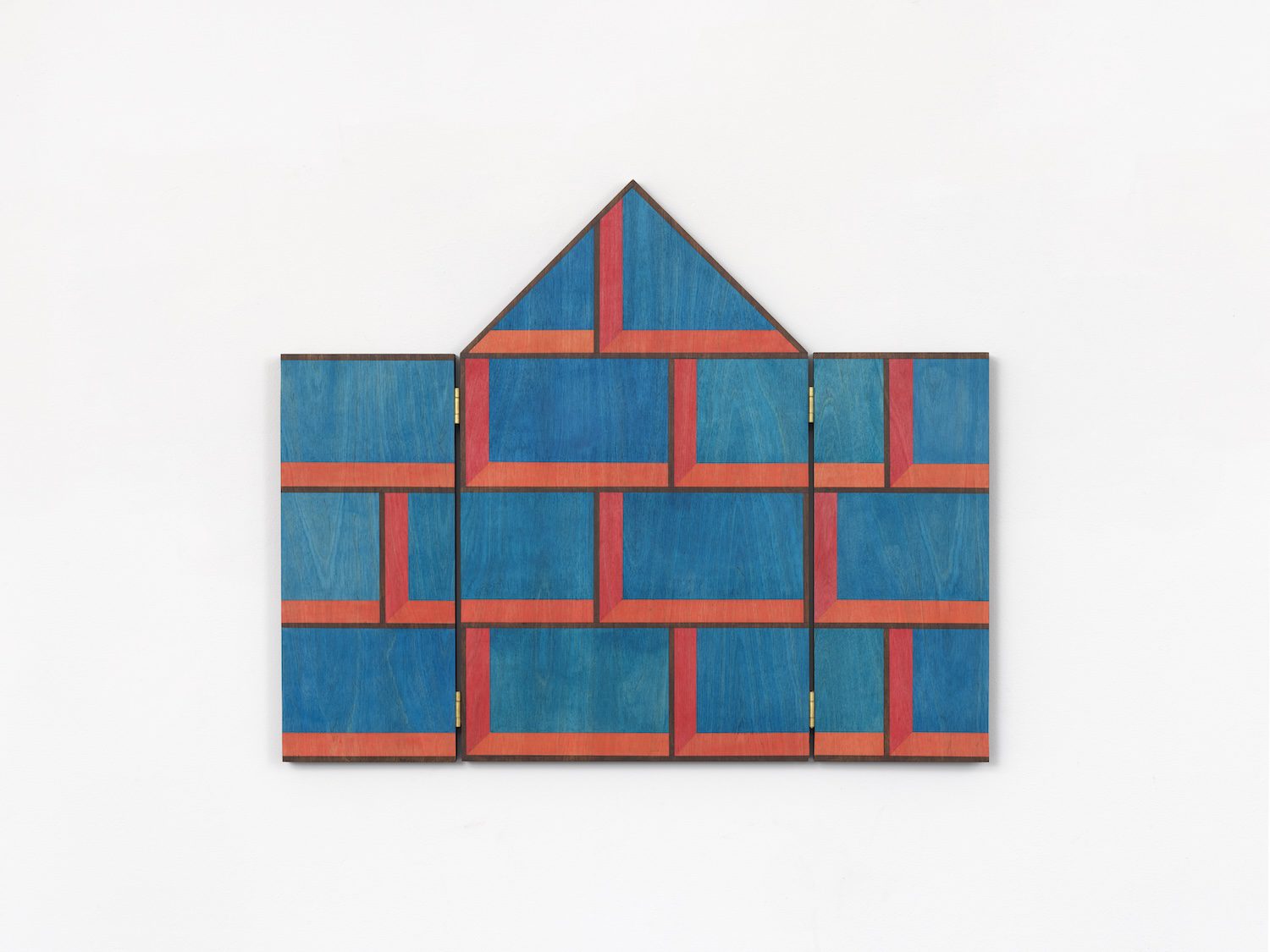

Variously sized, configured and painted in a mix of bright, matte, primary and secondary colours, the sculptures are replete with references to art, design and architecture: from shelves, containers and windows, to panel paintings, triptychs and floorplans. The hinges on the edge of the sculptures allows them to open and close, which visitors are invited to do. The sculptures are clearly restless things, at once playful and serious, calling to mind Marcel Duchamp’s famous observation that whoever is looking at the work of art completes it.

Whilst ostensibly abstract, Choi’s work makes clear that abstraction is a complicated concept: colours, lines and shapes will always, somehow, allude to something beyond themselves. The sky is seen through the rectangle of a window; the shelf is a straight line, a support and a showcase. As Rosalind Krauss observed: the grid is not simply the arrangement of lines, it ‘functions to declare the modernity of modern art’.

The word ‘maquette’ traditionally refers to a small-scale model, a rough draft of a sculpture or architectural design, which is used to visualize and test ideas, before the full-scale work is created. It’s derived from the Italian word, macchietta, meaning ‘sketch’. It occurs to me that what Choi is showing me is something of a riddle: sculptures that will, once displayed, be considered final, but which are, in fact, the embodiment of an idea in the process of becoming.

Choi mentions the Korean still life tradition of chaekgeori, which translates loosely as ‘books and things’ and flourished from the late 18th century to the first half of the 20th. Multiple versions of the paintings exist, each of which highlights a different configuration of variously coloured bookshelves. Choi says: ‘How you collect, sort, store and organize things says a lot about you. That’s why I found the shelf to be an exciting object that can be used to connect and address many things.’ The artist has also been inspired by the Italian studiolo – a small space set aside for study – which flourished in the 15th century. She says she likes to create imaginary connections between the Korean and the Italian traditions. Modernism, in Choi’s hands, clearly emerged from rich, cross-cultural traditions.

Describing herself as both a ‘substance and a filter’, Choi says she is ‘interested in certain historical spaces that have carried ideas’. Born and raised in Korea, she talks about herself as a ‘large container into which many influences have flowed from all directions and are flowing out again. Some have settled at the bottom. Others float on the surface. Still others are so well mixed with others that I no longer know where they come from.’

In many ways Choi’s sculptures are an enigmatic meditation on the idea of boundaries and borders – in other words, of the potential of, and resistance to, containment. Their suggestion of floor plans prompts a particular set of questions: who is allowed to enter this space? Who has access? Who is encouraged to stay? What does shelter imply? The possibilities are endless.

Text by Jennifer Higgie